Why Our Cognitive Biases Prevent Progress

"Our desire for conformity and harmony can be dangerous."

Last week, I introduced the development of the omnipartial individual series. This is the first essay in the series, and we’re delving into cognitive biases and how they shape our world. For an omni-win future, we need more than just political and cultural change. We desperately need to develop our skills and understanding of the world around us. It's the only way to strengthen our capacity to face complex problems.

Our entire democracy will only work if we commit to making it work. We have to collaborate with people we are afraid of, don't like, or trust. That can be scary.

Whatever your political concerns are, we can't let democracy fall apart. Our unwillingness to talk to each other could undermine the progress we’ve made. Everyone will suffer if we don’t grow in our capacity to deal with the tricky stuff and embrace uncertainty.

Why is complexity hard?

Neurobiology has the answer: We are hardwired to want to avoid complex things. Our fear of interacting with people who are different from us is innate. Evolution primed us to interact with people who look, feel, sound, and think like us.

We have ways to deal with complexity, and a whole world of cognitive biases constantly orbits our lives.

What are cognitive biases?

A cognitive bias is a tendency to think in a particular way that can lead to systematic deviations from rational judgment. They stop us from thinking logically about whatever's happening around us.

Some biases are information processing shortcuts where our brains just get to the point. Other biases are because our brain can't handle all the information that we need to take in.

Several cognitive biases are motivated by emotional or moral things. Others arise because storing and retrieving memories is an imperfect process. Our society influences several cognitive biases.

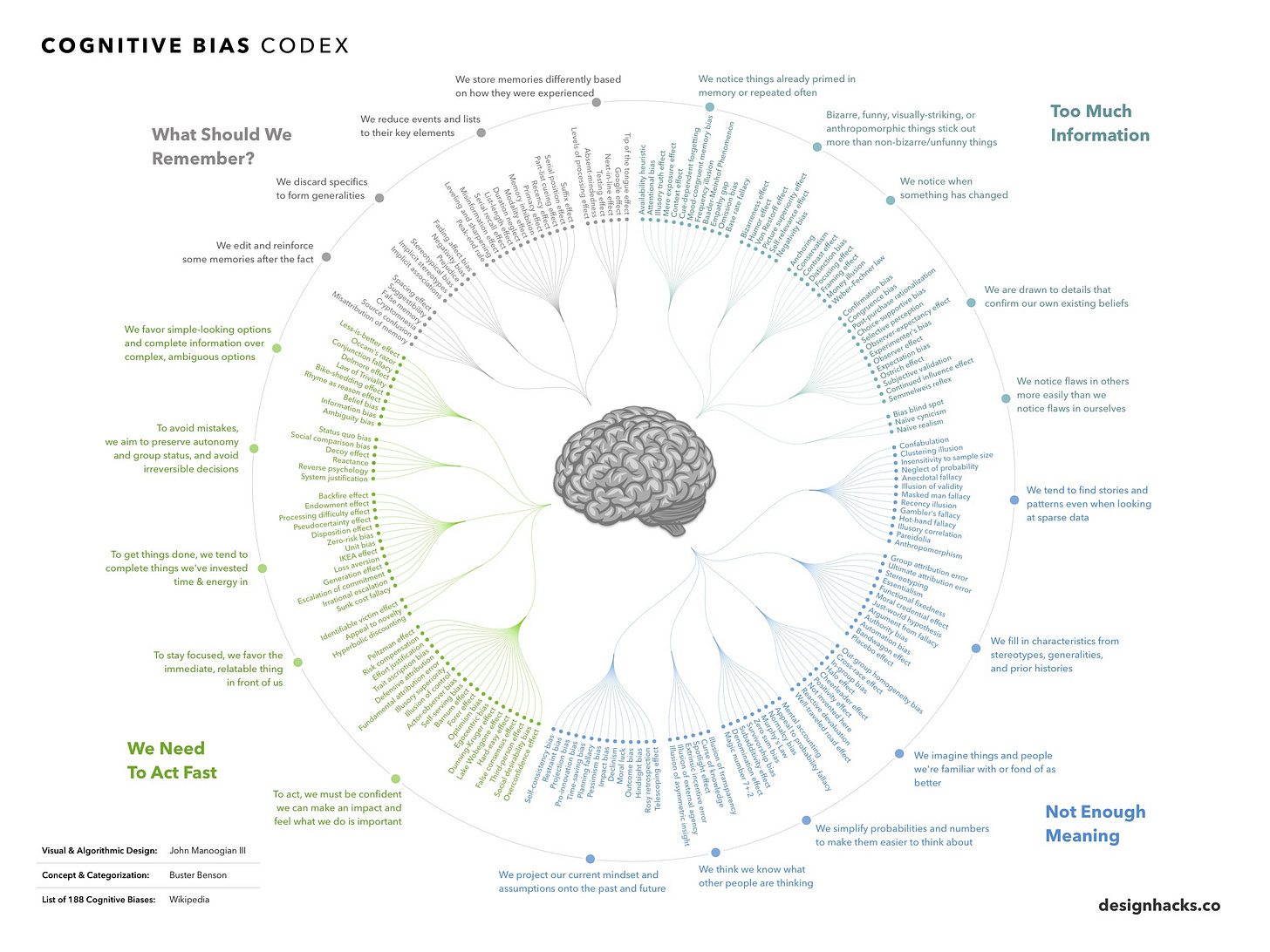

I recently discovered an infographic of 188 cognitive biases collected by Visual Capitalist and created by Design Hacks.

So, let's go on a tour of cognitive biases. Here’s the high-resolution version.

They have categorized these 188 biases into four main categories and 20 subcategories.

What should we remember?

We generalize and stereotype.

We need to act fast

We favor simplicity over complexity.

Too much information

We notice information that confirms our existing beliefs.

Not enough meaning

We think we know what other people are thinking.

Some cognitive biases affect our modern world and our political landscape. We favor our own group, and we’ll go along with whatever that group is saying to fit in. Our desire for conformity and harmony can be dangerous and push us toward doing certain things that we might otherwise disagree with.

Here’s another cool categorized bias infographic from Visual Capitalist:

Why am I showing you these?

Because cognitive biases are totally human.

They are hardwired, so we’re unaware we’re thinking this way. We should give ourselves a break sometimes. We can’t easily avoid these cognitive biases, just like any implicit bias, but we can be aware of them. Knowing and noticing when we’re falling into cognitive bias is really important so we can think logically about a situation.

Let’s look at a few cognitive biases

I attended the Summer Conference of the National Coalition of Dialogue and Deliberation a couple of weeks ago. Professor Martin Carcasson led the workshop “Reframing Democracy Through The Wicked Problems Lens.” He presented an excellent section on cognitive biases.

He broke down the “problematic” bias elements:

We crave certainty and consistency.

We filter and cherry-pick evidence to support our views.

We avoid dilemmas, tensions, and tough choices.

We strongly prefer to gather with the like-minded.

We are suckers for the good-versus-evil narrative.

We tend to crave safety, which comes from certainty and consistency. Naturally, we want to avoid negative experiences. This makes me think about Freud’s pleasure principle: Our innate desire to seek pleasure and minimize pain and discomfort. As we’re hardwired to prefer simplicity and clarity, we want to avoid dilemmas, tensions, and tough choices.

We are group-oriented, so we like hanging out with people who look, think, and act like us. Once we're in a group, we naturally develop a competitive group mentality. This translates into wanting bad things to happen to other groups of people. This becomes really relevant in our polarized society, and it gets even more amplified with political issues.

Of course, no one likes being wrong, so we tend to filter, seek, and remember the information that supports what we already believe. We want confirmation, and we’ll fight the things that challenge our beliefs.

When an issue crops up, you might think, “I’ll be open-minded and look at the facts.” But you have another cognitive bias to contend with: The “make sense stopping rule.” (Real catchy.) We look for information, find the things that we already agree with, and that's good enough. We stop there rather instead of taking in all sides.

There's also “motivated skepticism.” We all have a reason why we want to be skeptical of something, and we keep looking for the information until we prove we’re right.

Why do political issues feel like war?

The profound us-versus-them discourse in our politics lately has almost adopted a war mindset, full of ad hominem attacks, polarization, and disinformation. When we feel like someone is attacking our group, we might justify anything and throw ethics out. We may even attempt to overthrow democracy to ensure our group gets justice.

In episode two of the Omni-Win Project Podcast, Ken Cloke discusses the insurrection and how our divisive culture impacts democracy. You can find the podcast here. You can check out the Substack episode page for more highlights and clips.

I’d love it if you could join me in co-creating the future of democracy.

Thanks to evolution, your brain protects you from threats, and it’ll do whatever it can to keep you safe. Unfortunately, it doesn’t distinguish between physical and psychological threats. Did someone challenge your identity or understanding of reality? To your brain, that is just as threatening as a tiger jumping out of the bushes.

Our political issues are so intense because it's not just uncomfortable for us to be wrong and adapt a new piece of information. We might have to depart from the consensus thinking of the group around us. Opening up to other people's beliefs can threaten our relationship with the group. This is compounded by one of the cognitive biases that I find fascinating: The backfire effect.

I’ll be diving into the backfire effect in the next essay. There will be some interesting examples to see how you respond to new and unexpected information. Stay tuned.

If you prefer to watch your content, here’s a video on the topic of this essay:

Have you subscribed to the Omni-Win Project Podcast yet? Find it on your preferred platform and join the co-creation journey. Don’t miss your chance to make a difference.

Check out the new Omni-Win Project website and follow me on other platforms.

It would also be great if you could subscribe to my YouTube channel, where you can watch more of my long-form content, authentic discussions, and weekly videos:

You can schedule a call with me here: https://calendly.com/duncanautrey

Thanks for reading The Omni-Win Project! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Thank you for raising this topic of the link between biases, progress, democracy, and more. I have been struggling with understanding it for over two decades.

Neurobiology ONLY explains how hard it is for us to make effective choices for the SHORT TREM (!) when we have more than five choices. For the LONGER TERM, our brain can handle more than five choices.

So, we categorize things to make issues simpler for us to process and handle. Still, HOW we categorize and the particular ways we explain things, like our fear of interacting with people who are different, is in our hands. It is more cultural than biological.

The particular way we categorize and explain is not innate nor hardwired. Instead, the nature of our categorization and explanation relies on the cultural norms, assumptions, and habits we are embedded in. WE created hierarchical cultures wherein men are more important than women, white is better than black, and West is more important than East, so the good thing is that we can CHANGE it. There is HOPE!