"Unity, not uniformity, must be our aim."

How can we honor our differences and build a better future together?

Today, I’m going to talk about how we can unite across our differences. While it may seem easier to ignore and disregard the opinions of people we disagree with, this is corrosive and damaging to society. Our differences can actually energize us, especially if we find ways to integrate them.

Firstly, I want to share a quote from Mary Parker Follett. She was a philosopher and writer at the turn of the 20th century. This quote comes from her book, "The New State,” which she wrote in 1918. It was clearly way ahead of its time.

I've kind of become obsessed with this book and Mary, who's a total visionary. She had ideas that really align with the Omni-Win Project, which is why I want to share this with you. Here’s the quote:

Now, that's the main quote that people usually can find from her, but it goes on. There are some great thoughts here:

“We don't want to avoid our adversary but to ‘agree with him quickly’; we must, however, learn the technique of agreeing. As long as we think of difference as that which divides us, we shall dislike it; when we think of it as that which unites us, we shall cherish it.

Instead of shutting out what is different, we should welcome it because it is different and through its difference will make a richer content of life. The ignoring of differences is the most fatal mistake in politics or industry or international life: every difference that is swept up into a bigger conception feeds and enriches society; every difference which is ignored feeds on society and eventually corrupts it.”

There are two things that I want to lift out of this. First of all, being aware that ignoring, assimilating, or folding in differences is not helpful. Ignoring differences can be totally corrosive because it marginalizes people and pushes them away. Compromising, or just accepting differences, is also not the trick.

So, what is the trick?

Part of it is moving towards collaboration and making an effort to find the integration point of the differences. A little hint to the trick? Find the question that creates the difference to integrate the differences. Usually, if we find an either/or question, the answer is both and neither. If we're trying to decide between this or this, and it seems impossible, we need to discover the bigger question holding it all together.

The other thing that’s really powerful about this quote is that it lifts the importance of the generative power of differences. This is something that a teacher of mine, Diane Musho Hamilton, talks about with sameness and difference. I've made a video and article on this topic.

Including all the differences into a solution means that you've truly considered all the different perspectives. If only half of the people decide what's going to happen, it's not going to work, which inspired my second rule of conflict:

"Everyone who is involved in the problem has to be involved in the solution."

I often add the caveats, "or it's just not going to work," and "the people who you don't include are going to include themselves on their own terms."

So you might as well include them from the very beginning.

Yes, we’re diverse and polarized with different perspectives. But we can't make any changes without each other or solve problems without including the people we disagree with. So, we need to figure out how we will agree or work with our “adversary.”

Unity, not uniformity is our aim here, but how do we get unified across our differences? How can we have unity without needing uniformity? Or how can we connect across our differences?

We’re all right

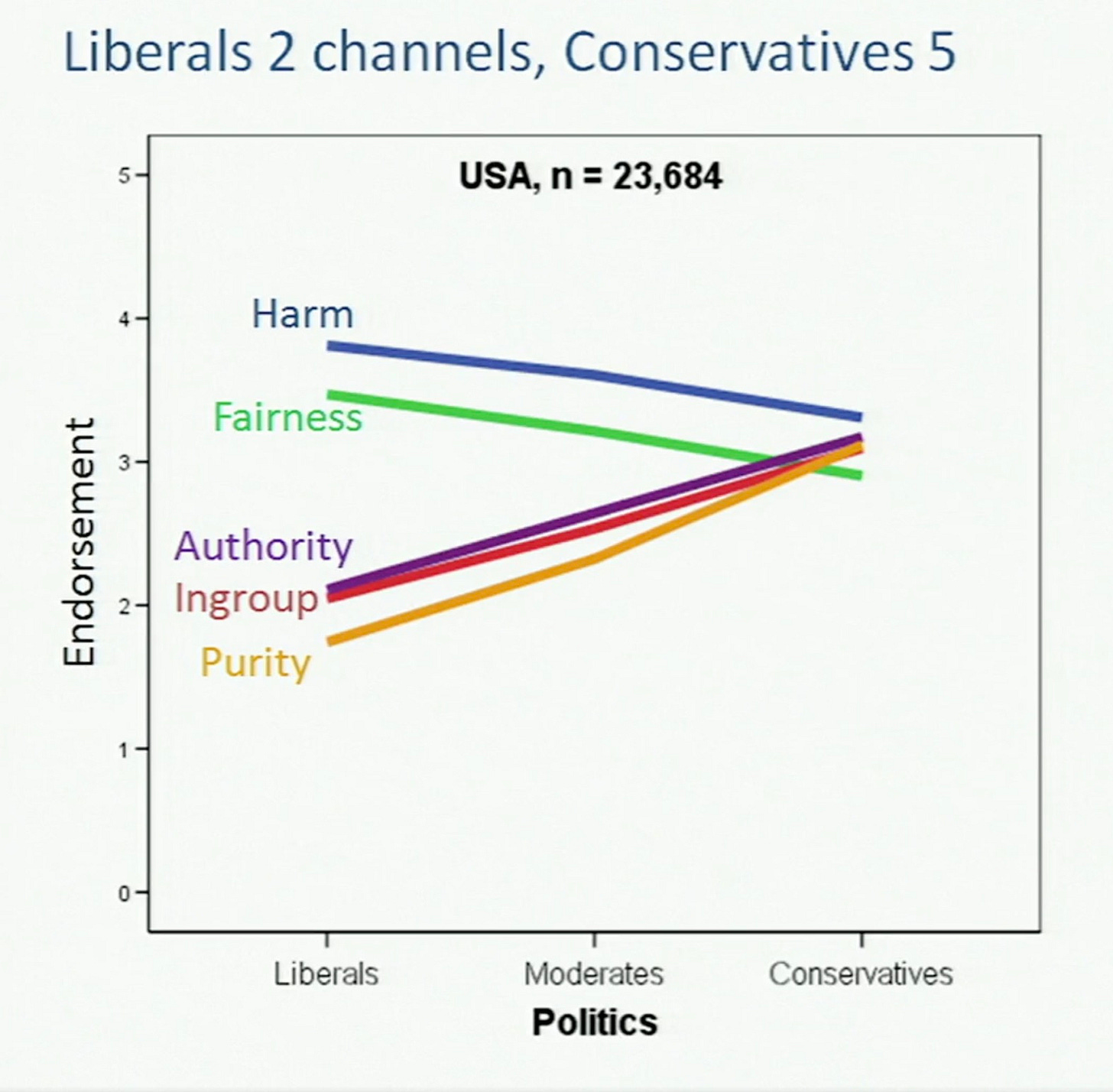

I want to recommend a Ted Talk by Jonathan Haidt called “The Moral Roots of Liberals and Conservatives.” Through lots of research, he’s pulled out a lot of great data, so we’re able to understand people’s political leaning based on certain moral values.

Generally, among liberals, there's a lot more openness to new experiences. Among conservatives, there's a lot more interest in order and traditions. While our intelligence and experiences have some influence, for the most part, lots of research shows that we're predisposed to lean one way or the other. So, we can let go of the idea that we can change people into thinking differently.

Another reason why we can't change people is that everyone knows they're right. Everyone knows the values and morals they're using to guide their life are the right ones. Otherwise, they wouldn't do it that way!

While we all have moments where we aren't acting in alignment with our values, we know what our values are, and we're pretty sure they're the right ones. Understandably, people aren't really open to being convinced that they have the wrong values.

(If you want to read more about how to deal with the internal experience of that, check out my post on self-forgiveness from last week.)

Jonathan says there are five moral foundational belief systems:

Care/harm

Fairness/cheating

Loyalty/betrayal

Authority/subversion

Sanctity/degradation

In all the research they've done, everyone was more or less on the same page about the importance of harm, and fairness. The real difference was in group loyalty, respect for authority, and the value of purity.

The right highly values those facets much more than the left. There was far higher interest in change and improvement even at the risk of chaos on the left. There’s a desire to have order and purity on the right, even if that means perpetuating past harms.

The “moral matrix”

As we organize ourselves into right and wrong around these different approaches, we create the misconception that people are either unintelligent or ignorant. Jonathan says we're “trapped in a moral matrix.” We're tricking ourselves if we think those people are doing it wrong, and these people are doing it right or vice versa. That isn't really what's going on. Different values guide everyone and all of these values are important.

(You can check out my full post with Bill Shireman quotes here: it’s full of enlightening topics.)

A great way to think about this is to look at this from a third perspective. We can ask, “What's the right way to be running our country?” If we start asking that question, some people might say, “Whoa, I see a bunch of problems, and we need to improve upon them,” or they might say, “Wow, what we have going on here is awesome, and we shouldn't risk changing it.”

The trick is both of these are noteworthy. We can't step into a new future without making some changes. However, if we don't stand with our fellow humans on the ground we're on with respect and gratitude, we're not going to be able to go somewhere else.

Steve McIntosh has done a ton of great work around this, and he was on my podcast, Fractal Friends, a couple of times. He's written a book called Developmental Politics and created an organization called The Post-Progressive Post.

There's great analysis about how it would look to integrate different values without uniformity while still holding diversity. One of the things this comes down to is the idea of interdependent polarities: In short, the desire to change, make progress, and step into a new way is interdependent with the desire to keep things the way they are. There are risks either way, and they both have their valuable side: one creates space for improvement and keeps things dynamic, and the other is stable and reliable.

Change or order?

So, we're in this tension between change and order, which will stick with us. The answer is not to choose one over the other. One of the most important things about interdependent polarities is that if you try to choose one at the expense of the other, it will become a destructive force. But when they work together, really amazing things happen.

Another interdependent polarity that Steve McIntosh teaches about is grievance and gratitude. This is useful for us to consider as we see things that we want to change, especially if we're trying to change our country.

What can we be grateful for?

What's going well?

How can I be not okay with the things that are not okay?

Let’s take the time to be grateful for things in our uncertain world. There’s always going to be tension and divergence of opinion, and it’s what we do with it that counts.

Yes, and?

I want to draw on a new tool I learned recently. This is from a man named Shirzad Chamine, the creator of the Positive Intelligence Program. He calls this the “Yes… And…” game. The idea here is that everything someone says is at least 10% right. Now, they might be way off base in whatever they're saying, but there's probably 10% that you can find to agree with.

So, if someone’s talking to you about something and you're really not understanding where they're coming from, you can try this:

You can say, "Yes, I agree with, [and then name the 10% you agree with] and I wonder if we can improve that by doing X, Y, or Z?" and that's where you add in your part.

Whatever's going on, find the 10% of something that you agree with, and affirm that. That will encourage them to engage with you and see how you can build on the 10% you already agree with.

If you can do this back and forth with someone, really amazing things can happen. You can even tell them what you're doing:

“Okay, you tell me something. I'm going to say, ‘yes,’ and say what I like about what you said, and then I'm going to add something so you can do the same.”

Their job is to listen to you, pull out what they think is good, and see if they can build off that. What's amazing is this can get extremely generative, and it’s a great way of brainstorming, thinking, or exploring new topics.

Why is this important?

Because right now, we have the idea that we're one side against the other. But we really need to figure out how to find win-win solutions, which is the heart of the Omni-Win Project. I talk about this a lot in an essay called We All Win, or We All Lose.

It's worth recognizing that there’s a connection from the win-versus-lose to the us-versus-them issue, which will lead us to the path of destruction. To pull back on Mary Parker Follett's wonderful wisdom here: the most disastrous mistake we can make in our democracy is to think our differences are the problem.

Our differences are not the problem: It’s our inability to connect across the differences. We must build a world that incorporates everyone's values, traditions, the past, and our hopes for the future. That's what we have to do.

That's where the omni-win is.

If you try the “Yes… And…” game with anyone, I would love to hear how it goes. Even if you just find yourself noticing, “Uh, gosh, I really don't agree with someone, but this one 10% I can get behind.” See how it goes. Leave me a comment below if you try it!

You can check out my YouTube videos that inspired this essay below:

You can find more information about the work I do in conflict transformation on my website: http://www.omni-win.com

You can schedule a call with me here: https://calendly.com/duncanautrey

Don’t forget to check out the rest of my posts as I discuss how we can work together to ensure we all win.

If you’d like to see more of these weekly round-up posts, subscribe to Omni-Win Visions here on Substack:

It would also be great if you could subscribe to my YouTube channel where you can see more of my long-form content, authentic discussions, and weekly content: