The Importance of Nonviolence

Spoiler: It's even more effective than violence in changing the world

This week, I’m looking at nonviolence. This awesome transformative process has a deep, intriguing history, and I’m making some recommendations here for you to learn more about it.

What do you know about nonviolence? There are many misconceptions about nonviolence, including that it’s incredibly passive. It’s definitely not! Keep reading to learn more about the nonviolence movement.

What do you believe is possible? Do your beliefs reflect the world you want to live in?

I ask these questions because I want to share a quote from Mohandas Gandhi, also known as Mahatma Gandhi.

There's an important question here that's important for me personally and for our culture nationally and globally right now.

Do you believe in your ability to change? Do you believe in other peoples’ ability to change? Do you believe that our culture and our systems can change?

Can we improve our political system and make our democracy work better? What would be the consequences of not believing that?

Hypothetically, following this Gandhi quote, let's just say that I believe the political system is busted, and we can't fix it because it's inherently wrong.

Firstly, my thoughts will run with that: I'll probably tell others and spread the word. As I talk to other people, I’ll act based on my assumptions. I'll be more self-protective and distrustful of others.

I won't believe that other people have good intentions. The people I distrust will respond by matching me there, and my beliefs will impact the younger generations. Eventually, this will become the value that guides me. Don't trust the system. Don't trust other people. Don't trust yourself. We're all stuck.

That will become my destiny, and I will step into the great unraveling. How do we avoid falling into a pit of despair and distrust?

I’d like to talk about a film called The Third Harmony. It’s about nonviolent resistance.

The three harmonies are:

Harmony with the earth and our environment

Harmony with other people

Harmony with ourselves.

They suggest five elements for harmony:

Avoid or be very cautious about your consumption of violent media.

What are your information sources, and what are they normalizing?

Learn some nonviolence skills.

Wonderful schools teach these, and I would recommend the Metta Center, East Point Peace Academy. It requires some discipline.

Learn nonviolent communication: Take a class on mediation.

You can also learn about restorative justice. It's a real up-and-comer. Restorative justice asks how we can restore our community back to the best situation that we want. This is a really important question for us.

Take up a spiritual practice.

That can mean whatever you want it to. It's helpful to have capacity for mindfulness and a meditative state to find equanimity in the face of challenging situations. It’s nice to feel like we’re not alone.

If you're feeling divided or you don't like someone, figure out how you can relate to them on a more personal level.

“Break bread,” that's a good way to think about it. Go on a walk, talk about a common interest. Humanize them.

Figure out what’s aligned with your values.

Start a project, dedicate yourself, find something that relates to whatever it is that you want to pursue in this world, and do something about it.

The Three Harmonies director, Michael Nagler, says:

"If you start from the assumption that everybody has a good core in their nature, that we are all deeply connected, and that there is no problem which cannot be resolved to benefit all of the parties…

If you start with those assumptions, and even if you don't believe that, you can take them on as a hypothesis and as assumptions, and as you test them, you will find out that it works."

So my question for you:

What would it take for you to believe in inherent human goodness?

I want to share something from Kazu Haga, again from The Third Harmony. He says:

"A core principle or a worldview of nonviolence is the unwavering faith in humanity and in the goodness of people. It's grounded in the belief that transformation and healing are possible."

This is where we start with the belief that transformation and healing are possible: That there's goodness in everyone. Now, perhaps that's a little challenging for you. Maybe you believe we're separated or that violence is an inherent part of humanity. I'll point out two things.

Through science, religion, and philosophy, there is plenty of evidence that we are not separated. We are all connected, interdependent. You couldn't ever really parse out anyone from their context, so we're not separated, that's for sure.

Kazu also referenced a story he heard from a soldier who pointed out that every human being is traumatized by violence. Violence is traumatizing whether you witness it, do it, or receive it. It is not in our inherent skills.

I personally believe that everyone wants peace. Short-term things may distract people from that, but I'm pretty sure we can all get behind the idea of building a world that is as good as possible for as many people as possible.

I believe anyone who doesn't agree with that is in need of healing, and they deserve our love, compassion, healing, and support. It's not their inherent truth. I have good evidence that we have all the tools we need to start creating a culture, system, and democracy that addresses everyone's needs, allowing the participation of everyone.

We need to demonstrate the power of these tools, and show people they are available. I find it confusing that we don't use all of these wonderful conflict resolution, dialogue, and consensus-building tools to heal our democracy. We're very much in need of healing, and there's a huge desire for this change to happen.

My hypothesis is that either people don't know that these tools exist, or they know about them but don't believe they're actually real. Personally, I want to change this. Picking up Gandhi's quote, let me show you where my belief takes me.

I really believe things can improve. I believe our democracy can improve, and I believe that learning how to communicate better can fix almost all the problems that we're facing, whether it’s terrorism, the oceans, climate, our police, or the justice system.

I believe all of that can change, and we have the tools to fix it: I see evidence for that everywhere. It inspires me to learn new skills and information. A lot of what I'm sharing with you here is because I believe in the importance of spreading the word about these conflict resolution tools and amplifying the message.

I also believe in acting to make this change, to support this healing, and I've been doing this for a while now. It’s created repetition and a habit. I really can't tolerate hearing about ineffective conversations, political indecision, people getting stuck on certain things, or the whole us-vs-them issue. I'm not okay with that anymore when we have these tools at our disposal. It has actually become a value of mine.

The value is called omnipartiality: A bias in favor of everyone. I am partial to everyone and that guides my thinking. In the last year or so, I decided to make this my destiny. My life path is very clear: This is something I'm excited to bring into the world, and I have a sense of purpose here.

Part of my destiny is the Omni-Win Project. My essays and videos are just the beginning of this. I'm still getting things up and running, but I have a podcast coming for you, a website, and all sorts of resources. I really want to help us co-create the world where everyone wins. Because I believe in it, it's becoming my destiny.

What would it take for you to believe that a win-win (omni-win) future is possible? Please share your thoughts with me here. This isn’t a rhetorical question.

To create an omni-win future, nonviolence is the way. Gandhi’s quote is a perfect example of nonviolence: It demonstrates what it takes to build the future that we're trying to build into our current actions. There's a certain alignment of the ends and the means, and it takes great belief to get to the actions which create the destiny.

Gandhi was an incredible figure. Einstein said that people will barely be able to believe that this person even existed. Gandhi is one of my heroes, but even he didn't learn about nonviolence all by himself. There was a long history that got him there.

So, that brings me to my first recommendation of this essay. There's a podcast called The Thread by OZY Media, and they take a certain moment in history and follow it back through time to find out how it came to be.

On their episode, A History of Nonviolence, they start with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr using nonviolence to transform racial segregation in the south. Initially, Martin Luther King didn’t truly believe in nonviolence. While he wasn't going to go out there and try to use violent revolution, he wasn’t sold on the idea until he met Bayard Rustin, a gay, black civil rights activist. He was raised and trained by the Fellowship of Reconciliation on how to do nonviolence, so he's the one who taught Martin Luther King how to do nonviolence.

Within a couple of weeks of meeting him, Martin Luther King got rid of all his guns. Rustin was a ghostwriter for many of MLK’s speeches and the organizer of the March on Washington. Rustin went to India and met with Gandhi, and he was a huge influence.

Now, Gandhi started as a lawyer and didn't necessarily understand nonviolence initially, but he noticed it was much more effective. Gandhi was very moved by Leo Tolstoy, the author of War and Peace and Anna Karenina. From his perspective, his master life work was a book called the Kingdom of God is Within You, a treatise on Christianity. It was based on the Sermon on the Mount by Jesus. It was Tolstoy’s way of saying, wait a minute, Christianity says we're supposed to resist the system and not tolerate injustice, oppression, and all of that.

But guess what? Tolstoy didn't get it on his own either. He learned from William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison was a Quaker and abolitionist in the United States. Obviously, there are various abolitionists, but Garrison really stood out. He believed in true equality and nonviolent resistance to slavery and all forms of oppression.

He created a newspaper, The Liberator, in which he shared stories from slaves and published them. It was one of the few places that slaves' narratives were printed. Even though he was a white man, his readership was 75% black. Although slavery needed a civil war to end it, Garrison’s insistent message was a huge motivation for Tolstoy who was in correspondence with Gandhi and others.

Now, Garrison couldn’t do what he did without the help of an African-American businessman, James Forten. Forten was born a free man in Philadelphia in 1766, and he was really psyched about the United States throughout his life. He fought in the Revolutionary War, but he was captured on a ship, the Royal Louis, by the British. He was only 14 years old at the time.

The captain of the British warship had a young son with him, and Forten played with his son, creating a wonderful friendship. This inspired the captain to not sell him into slavery in the West Indies, and he treated him as a normal prisoner of war with the other captives. He got lucky as he was exchanged after seven months' imprisonment.

In 1831, Forten’s money brought The Liberator into existence, inspiring the nonviolence of today. Hearing this story, I noticed that there's something a little deeper here. How was it that the Quakers became so antiwar, one of the few antiwar churches?

Digging back a little bit more, we can find a Quaker friend named George Fox, who spoke out for peace and against war in 1651. His thinking was that Christianity needed to be a practice, not dogma, or some ideological system that explained how things were supposed to be.

He really believed it was contrary to the spirit of Christ to use war and violence to deal with the problems in the world. Of course, that was similar to the view Tolstoy came to. All this prompted me to look at Jesus's Sermon on the Mount, specifically the Beatitudes, which aren't just from Jesus: Those come from the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament.

It lifts up everyone:

Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted. Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth. Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled. Blessed are the merciful, for they will be shown mercy. Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God. Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are you when people insult you, persecute you and falsely say all kinds of evil against you because of me.

Now, all of those are qualities of a nonviolent practitioner. It makes sense that Tolstoy picked that up and said, wait a minute, we can't be going to war for Christianity.

As I was digging into this more, I also learned that Jordan Peterson has dug into this “meek shall inherit the earth,” and he found that some of that earlier Greek translation of meekness, meek means something closer to “those who have arms and weapons and the skills to use them, but choose to keep them sheathed.” Again, I think this speaks to the power of what nonviolence is. It's the ability to make change, there's a power behind it, and there’s the choice to not use it.

Violence is always available, but the choice to respond to violence with love takes a whole other level. Now, just in case we're got too much down in a Christianity path here for your liking, I'll just point out that Gandhi said "nonviolence is as old as the hills." And the Buddha said "for hatred does not cease by hatred at any time. Hatred ceases by love. This is an unalterable law."

What we're really pointing to here is the force within each of us to love and to be good. The “weapon” here? Trusting that force of goodness is inside of other people.

I learned something really interesting from Mark Kurlansky's nonviolence book, 25 Lessons From the History of a Dangerous Idea. The first thing is, there's not a proactive word for saying nonviolence. We have to say nonviolence. This is why people who support nonviolence really want it to be one word instead of with a hyphen in there. That way, we can really indicate that it’s not just the absence of something and we're actually proactively doing something.

In Hinduism, there's a concept of ahimsa: “Himsa” is harm and “ahimsa” is non-harm. It also points to something that’s proactive. It means the creative power that arises when you control your intentions to do harm. Gandhi created the first proactive word for this, which is Satyagraha, which I've heard translated as “truth force.”

It wasn’t until 1920 that we even had the word nonviolence in English. So this is a fairly new thing that's evolving, which is why it was so awesome that people took this timeless idea into modernity. So that brings me to my next recommendation:

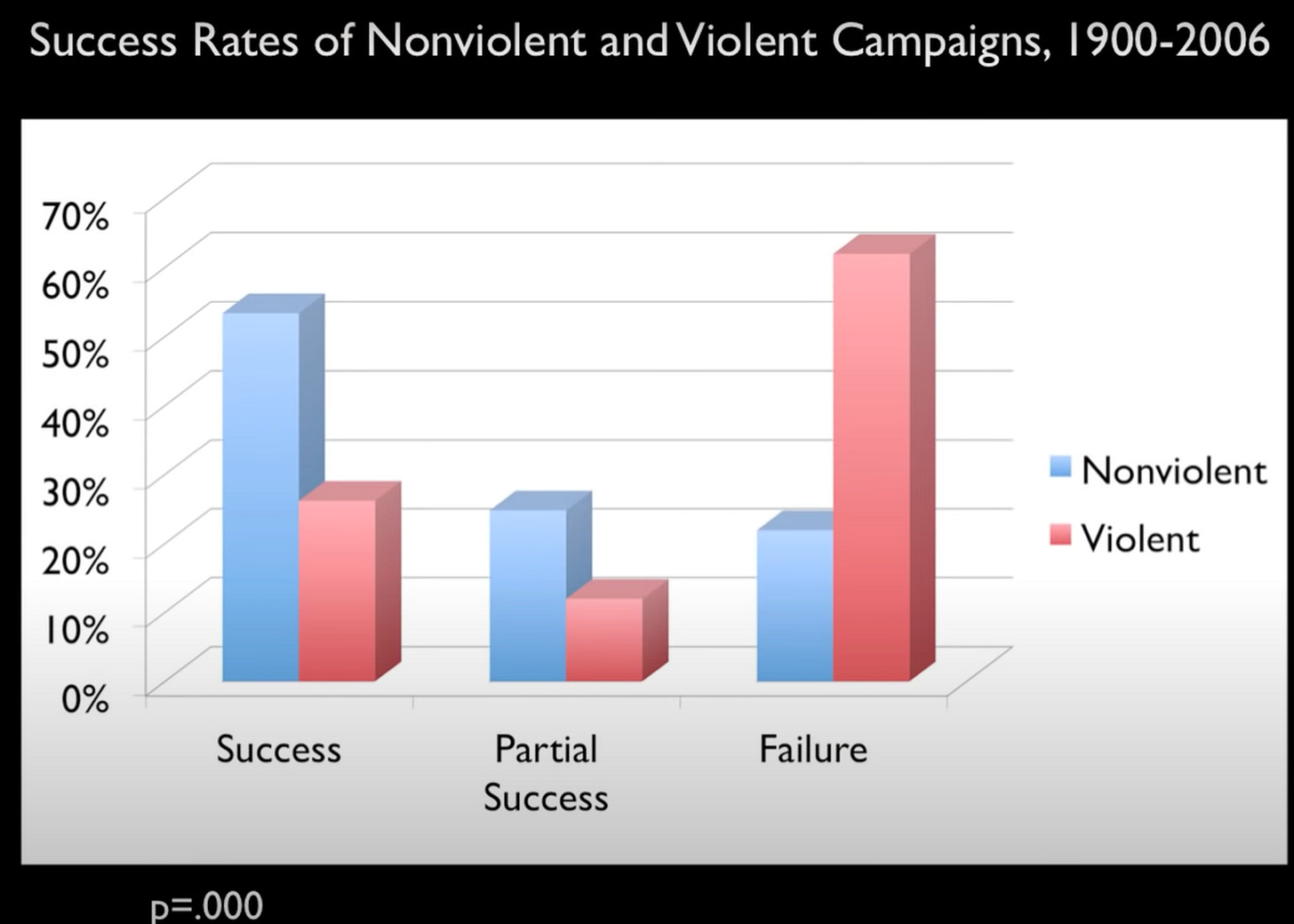

There's a woman named Erica Chenoweth. She was at Harvard wanting to study terrorism and trying to prove that people who use terrorism and violence might have a good reason for it, and she thought that nonviolence was some sort of hippy thing. Maria Stephan was another academic who joined her and said, let's find out if it's true or not.

They did a statistical analysis of case studies of every revolution that happened on the entire planet between 1900 and 2006. Guess what they found out? Nonviolent resistance and its campaigns are twice as effective as their violent counterparts in achieving their goals.

What's more is that nonviolent revolutions create more durable, internally peaceful, democratic organizations, and they're much less likely to regress back into civil war. That's not all! Nonviolence works even when it fails. So even if nonviolent protestors don't turn over the system that they're fighting against, the culture and laws change and people's standards are raised.

Nonviolence is two to three times faster at achieving the goal than violence. It takes more or less three to four years for nonviolent revolution and violent revolutions usually take nine to ten years. Ten years is a long time to be killing for the world we want.

So how does it work? Nonviolent movements have a lot more participation: They’re four times as large as violent resistance. That's because it's morally and physically more accessible. It doesn’t matter if you’re young or old, people are able to participate much more easily, making it more visible. It also means that people from different walks of life are more likely to have connections with the people who are a part of the oppressive system. That creates shifts in loyalty among the opponents. There's an anecdote of someone refusing to shoot at a crowd because they think their children might be in there.

Here's the best part: Nonviolence is getting better. We're getting better at this, it's more effective, and more popular right now. In active revolutions, nonviolence is outdoing violent revolutions by two to one.

I highly recommend you check out the work of Erica Chenoweth if you find this to be surprising: here’s her Ted Talk. She co-authored a book with Maria Stephan called “Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict.”

I’m not saying nonviolence is easy. It takes discipline and dedication. You have to really believe in it, and you have to be willing to get hurt sometimes. That was the thing that I noticed when I listened to The Thread’s History of Nonviolence, everyone took hits. So it's not easy, but it works. Why?

Because it lifts up the people and the oppressors, showing them their humanity and reminding them of the world they want to live in, laying the foundation for the world we all want to live in. As with nonviolence, the means for getting change becomes the same as the ends that we're trying to get to.: That's inclusion and nonviolence and peace. This reminds me of the third rule of conflict.

In my work doing conflict transformation, I've discovered three rules of conflict. The first is that it's not about what it's about, the second is that whoever's involved in the problem is going to have to be involved in the solution. And the third, which I'm going to talk about today, is that the process for transforming the conflict is the same as the outcome.

So what do I mean by that? It means that the process for transforming a conflict, the very choice to engage in the process of making a change, is the beginning of a new way of being in relationship. Another way to think about that is the qualities and intentions we use in the process are going to be infused into our outcome.

This comes back to the quote we started with about belief creating destiny. The ways we act with each other will inspire the ways we continue to act with each other.

Here’s a little quotation here from Thomas Merton, who wrote the introduction to Gandhi on nonviolence.

“Peace cannot be built on exclusivism, absolutism, and intolerance. But neither can it be built on big liberal slogans or pious programs that are just stated in the smoke of conflaguration.* There can be no peace on earth without the kind of interchange that brings man back into his right mind."

*Conflaguration means deception or a difficult situation

We know that we can't build the future that we want if we're trying to be exclusive, absolutist, or intolerant. Fluffy soundbites aren’t going to get us there, nor are lies or deception.

So how do we do it? We have to do it ourselves. Now, this is a big thing to think about, but it really is about me and you and us. We're the ones that right now are building the future that we want to live in. That's a big one. So how do we do that? What would it look like for us to start building a future that we all want to live in right now?

So I'm going to share a bunch of ideas that I've collected. I'm sure there are more. If you have other ideas about what you can do right now to make a change and start building the world you want to live in, please share them. I’d love to hear about that.

Here are a couple: One, a theme that came up a couple of weeks ago: self-reflection and self-forgiveness. It's actually a lot easier and way more efficient to shift from trying to figure out how to fix all those people out there, surely they need fixing, but to first start with figuring out how to fix ourselves. And this means owning our own contribution to whatever harm is happening or whatever it is we don't like.

And also paying attention to our own contribution to the healing that is possible. Another quote here. "If you aren't part of the problem, you can't be part of the solution." And so recognizing the way that you're part of the problem too, and finding your forgiveness for that is the wonderful foundation for starting to build the world you want to live in. A way to actively do this is to use I-statements.

I-statements tell better stories. They're much more engaging if I say, I did this, this is what happened to me, as opposed to, you know what happens to people in these situations. That's not as good. But they're really important because you're owning your own story, your feelings, my feelings, my experiences, my requests, my desires. By owning that, um, I am taking responsibility for the world that I want to live in.

So, what do I do with these other folks? Deep listening. That's the second one. We just practice listening and I'll just go quickly through how this works. First of all, empathize with the other person. Um, show that you're curious by asking them questions, and use reflective listening. It's a really great skill cause you really want that other person to feel heard because you like feeling heard, other people like feeling heard.

Next thing: insist on inclusion. If you're being part of something that's trying to make change, who's missing? Why are they missing? Figure out how to remedy whoever it is that you're deciding to exclude from your change vision, because their perspective is going to be important too. One trick on how to do this is to try to figure out what the underlying question is that everyone who's involved can agree with.

So instead of trying to say, how do we change this? Or how do we create this set of rules or this new thing? Instead try to figure out what is actually trying to be addressed here and look for the question that everyone wants to answer.

A question that everyone might be interested in is like, what will it take to create a sustainable future for our country in the world, such that our grandchildren will be living great lives, you know, that might be something that people can get behind.

Another piece that's interesting, from a woman named Barbara Deming, she calls it the two hands of nonviolence. Basically, the first hand is stop. It's saying, “I'm not going to cooperate with situations and systems that are not just, that are not okay, that I don't believe in.” Develop your capacity for not tolerating crappy situations.

The other hand is the open hand and it says, “I'm open to you as a human being. I love you, no matter what.”

In summary, this Two Hands Nonviolence is to stop tolerating unjust and ineffective systems, and be open to the inherent human goodness that's inside of everyone.

This quote came up in my quote of the day calendar, and I thought it was really great:

"It's a bit embarrassing to have been concerned with the human problem all of one's life, and to find that the end, that one has no more to offer by way of advice than try to be a little kinder." - Aldous Huxley

If nothing else just ask, “Is what I'm seeing kind? Am I acting with kindness?”

If you want a world that's kind in the future, start practicing that right now. I'm asking this of you and sharing this because I think we all need to be participating in the creation of the world we want to live in.

In my conflict transformation work, people often ask me, “Do you believe peace is possible? Do you think there's going to be an end to conflict?” It depends how you think about it.

There are two parts to this. First of all, we're not going to get to the end of conflict. Conflict is an ongoing thing: As long as we have diversity, we're going to have conflict. Disagreement is a normal thing, but conflict does not have to be a painful experience. We get to make an active choice. Do we want this experience of being in difference to be painful, to cause harm and destruction? Or do we want this to be an opportunity for healing, learning, and generative co-creation?

Another reason why I'm not really sure if we're going to get to the end of conflict is because there might not actually be an end, which comes to the other part of the third rule of conflict and why I say the process and the outcome are the same is because the end of the process isn't a fixed state. It is going to be another process. We're just gonna say this process is inadequate. We're going into a new process and hopefully it's more adequate, but that process is going to keep on continuing. And that leads us to what I call the fourth of the three rules of conflict, which is there's not going to be a final outcome.

So again, we are the ones who are responsible for building the future we want to live in. You are responsible for building the future that you want to live in. So I ask, what are the qualities and the values that you want to see in this future? And then how can you infuse your actions right now with those values, beliefs, and qualities?

This is not a hypothetical question: I would love to hear your answers to this. What is something that you can do right now that's going to help you create the future that you want to live in? Leave your comments here.

You can check out my YouTube videos that inspired this essay below:

You can find more information about the work I do in conflict transformation on my website: http://www.omni-win.com

You can schedule a call with me here: https://calendly.com/duncanautrey

Don’t forget to check out the rest of my posts as I discuss how we can work together to ensure we all win.

If you’d like to see more of these weekly round-up posts, subscribe to Omni-Win Visions here on Substack:

It would also be great if you could subscribe to my YouTube channel where you can see more of my long-form content, authentic discussions, and weekly content: