🎧Ep21: Three Reasons to Celebrate Thanksgiving

A call for healing, connection, and breaking the cycle of violence.

This week’s essay is a little different: I’m creating it in tandem with a podcast episode and video. In this episode, I’m sharing three ways to celebrate Thanksgiving that are traditional, culturally respectful, and can generate true healing and reconciliation. You can keep on reading, listen to it, or watch it here:

Finding a shared narrative around the history of our country is a serious challenge in general, and Thanksgiving is a story we particularly struggle with. Why?

Because many of us are under the illusion that there can only be one of two stories:

Thanksgiving is a celebration of brotherly love and unity, remembering a time of mutual support between English Pilgrims and Native Americans.

or

Thanksgiving is a reminder of colonial oppression and covers up the horrendous genocide of Native peoples by European immigrants. Plus, almost everything we remember about that day is historically inaccurate.

This conflict between these two stories is a microcosm of a greater tendency toward polarization in the U.S. Trying to sort ourselves into good guys and bad guys is destroying our country and threatening our future.

Our world is complex. U.S. history is complex. Thanksgiving is complex. The desire to make any of it into a clear binary distinction is not only unproductive, but it’s also corroding our hearts and preventing the healing and unity that we all want and need.

So, where do we go from here? I believe there’s a way to understand Thanksgiving that can help us heal our nation and work toward a future that inspires us. And you won’t need to give up on your favorite recipe or sense of tradition. Let’s dive into it.

Where does Thanksgiving come from?

Let’s go for the abridged version:

Two traumatized communities made an improbable choice during a time of profound destruction and domination. In the Fall of 1621, a group of English separatists and economic refugees and a large group of the Wampanoag tribe reached out across language and culture, overcame distrust, and decided to cultivate connection and pledge mutual support despite their differences. Unfortunately, there is little record of this gathering, but we know it happened. We have two primary sources: A letter from Eduard Winslow and a journal.

Here’s what we actually know about the gathering:

After a successful harvest of corn and barley in the first year on land, the governor of the Plymouth Plantation, William Bradford, declared a “special celebration.” He sent out four men on a successful fowl hunt. 90 Native men joined at least 50 Englishman, and they hung out for three days. They feasted, shot guns, and played games.

During the event, the Wampanoag folk hunted five deer to add to the feast. They drank ale that the English produced from their only successful European crop. The groups didn’t think about it as a Thanksgiving, but it was definitely a celebration of the harvest.

This gathering happened in the context of a treaty of peace and mutual support, which they held to for the rest of their lives until 1661. That makes it the only treaty between English and Native folk that was kept throughout the lives of those who signed it.

Their gathering seems to have been a genuine cross-cultural peaceful interaction. It stands out as a point of light and inspiration in the arc of an otherwise dark and complex time in history. We remember this day 401 years later because it proved to be an exceedingly rare moment that took profound courage. It is a beacon of hope that we can connect across differences, even when those around us are at war with each other.

It was especially remarkable because of what preceded and what was to follow.

What came before?

The “Pilgrims” of Plymouth were separatists from the newly formed Church of England. They left England, fleeing religious persecution, and initially fled to the Netherlands. There, they lived with freedom but in abject poverty. What’s more, the Thirty Years’ War was just beginning in Europe. Their journey to the Americas was primarily as economic and war refugees and was financed by a group of 70 London businessmen called the Merchant Adventurers. They were indebted servants until 1648. Their journey across the Atlantic on the Mayflower was long and harrowing.

The Wampanoag people, also called “the People of the Dawn,” trace their history on what they call Turtle Island, now known as North America, back over 10,000 years.

Three to four years before the Pilgrims arrived, the Indians of southern New England had been decimated by diseases introduced by European explorers. Historians estimate as many as three-quarters of the Wampanoag people died before the puritans arrived.

The Englishmen settled in an abandoned Native American village called Patuxet. “When Europeans founded Plymouth plantation amid the ruins of Patuxet village, a Wampanoag village, they found the human bones littering the ground because no one was left behind to bury the dead.”

Why you should care

This moment of unity amidst great suffering is worth remembering. It could so easily have been lost in the whirl of a much larger tragic story that is still unfolding today. We are trapped in a cycle of generational aggression and trauma, and breaking out is the burden and responsibility of anyone who refuses to pass it on to the next generation. Thanksgiving traditions contain the seeds for resolving and healing some of the greatest wounds of humanity.

“Mary Had a Little Lamb” and genocide

Abraham Lincoln created Thanksgiving during the Civil War in 1863 through a Declaration. It happened because of the lifelong advocacy of a woman named Sarah Hale. She was an American writer, an activist, and a women’s historian. Hale was the editor of Godey’s Lady’s book and the author of “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” She insisted on the importance of a day of unification and peace for all Americans to celebrate.

By 1863, however, there were barely any Native Americans around to join this celebration. The destruction of the Indigenous population of this continent was almost complete. Before the arrival of Europeans, 5–15 million people were living in North America. By the time of the Thanksgiving Proclamation, the Native American population was around 238,000.

The loss of 95–98% of Native people can only be called “genocide,” defined as “acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group.” Their deaths were not only the result of disease but also the 1,500 wars, attacks, and raids authorized by the U.S. government. The genocide also included boarding schools for Native children designed to “civilize and assimilate” Native Americans, forcing children to give up their languages and religion. Let’s not forget the eventual forced relocation and ongoing displacement of almost all Native people on the East Coast.

This process of obliterating people they perceived as “savage and barbarian” didn’t come from nowhere. The Romans took the same approach as they conquered the Indigenous European people. The term given to the Romans’ approach to war is “Bellum Romanum,” which translates as Roman War. It derives from the approach adopted by the Roman legions when fighting against those they considered barbarians: People not deserving of civilized consideration. It is war without rules or restraint.

The Roman conquest killed and enslaved untold millions of tribes and cultures that we now call Celts and Gauls. On the British Isles, the Britons’ Indigenous culture was destroyed 1600 years before, beginning in the year 43.

In the 400s, the Anglo-Saxons, who were victims of the same genocide at the hands of the Romans centuries earlier, used the same all-out war approach when they conquered modern-day England.

Bellum Romanum is how many fought during the Thirty Years’ War between Protestants and Catholics in Europe. It’s still considered one of the longest and most brutal wars in human history. This was the context for the arrival of tens of thousands of Puritans, beginning in 1630, a decade after the now-famous harvest celebration at Plymouth (Patuxet).

The Puritans, loyal to the Church of England, were not the same as the “Pilgrims,” who were separatists. “The Puritans explicitly rejected religious freedom and never attempted to adopt the Pilgrims’ initial, fleeting cooperation with American Indian peoples.” Puritans of the Massachusetts colony numbered 20,000, while humble Plymouth was home to just 2,600.

The Puritans brought Bellum Romanum to the Wampanoag

In 1637, seeking revenge for the death of a man named Pequot, the settlers attacked a nearby Wampanoag village. They assaulted them in the early morning, telling them to come outside their homes before shooting and clubbing them to death while their people watched. The rest were burned alive and enslaved. They killed 500–700 men, women, and children. The Pequot War was one of the bloodiest Indian wars ever fought.

The next day, John Winthrop, the governor of the Massachusetts Bay colony, declared “A Day Of Thanksgiving.” This was the first time Thanksgiving was officially named and declared in the United States, and it was based on a massacre of Native Americans.

Cheered by their “victory,” the brave colonists and their Indian allies attacked village after village. Women and children over 14 were sold into slavery, while the rest were murdered. Boats loaded with as many as 500 enslaved people regularly left the ports of New England.

How to break the cycle of violence

I’m not sharing all of this to assign blame. Nor am I trying to diminish the horrors of European conquest. I’m putting things in context because there is a greater human story here.

Here’s the upshot. Many want to make sure our Thanksgiving feasts don’t cover up the genocide of the Native Americans. Many prefer to avoid facing the reality of that horrible past. The reason for both approaches is the same: We all know that the cycle of violence, the oscillation between oppression and trauma, needs to stop. We must break free of this pattern because it goes far beyond English settlers and Native Americans.

Every choice to dehumanize another person, people, or group and harm another with righteous justification or pursue our own needs at the expense of others feeds into this cycle. Simply developing a good-versus-evil narrative or embracing the identity of “us the victims” and “them the oppressors” keeps the cycle of violence alive.

This dynamic is alive and well in our modern-day culture. It’s infused into our politics, and it seems to be why over 40% of U.S. Americans think it’s at least somewhat likely there will be another civil war within the next ten years.

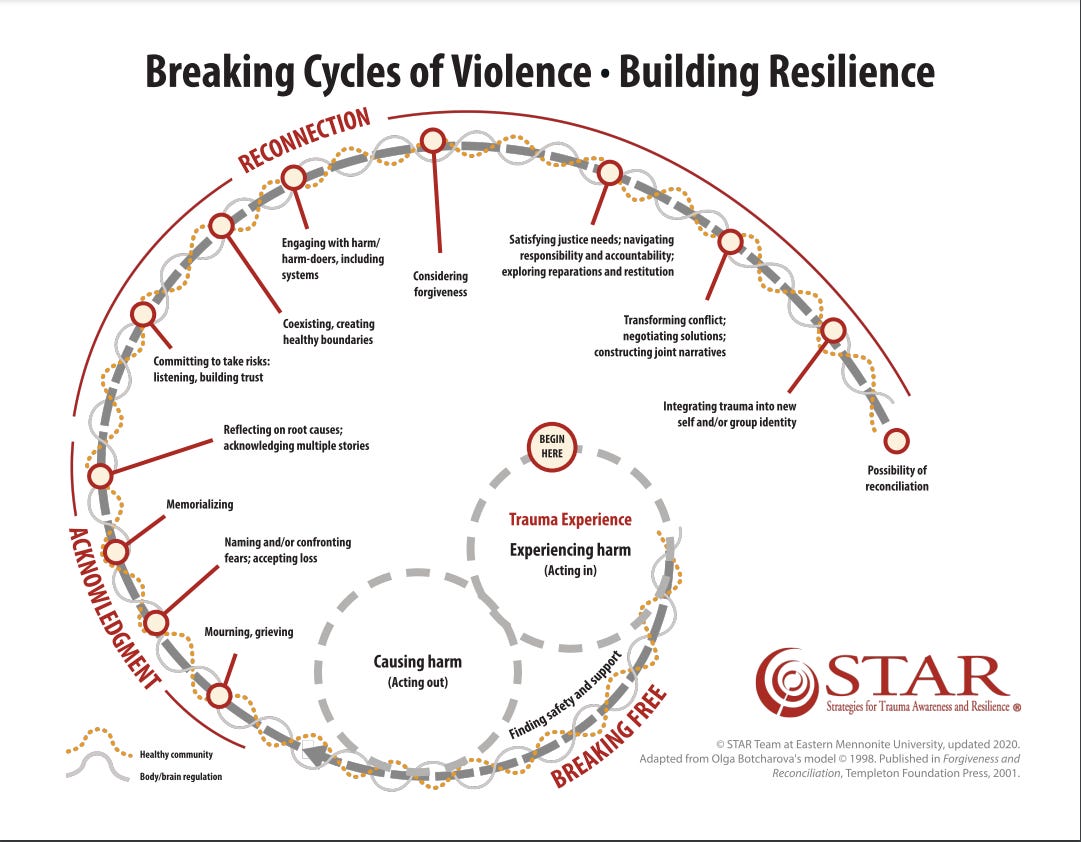

The cycle of violence has two interdependent sides: Causing harm and experiencing harm. So the suppression of grief, the feelings of guilt and shame, and nurturing fantasies of revenge are also feeding into the cycle. There’s also the sense of being helpless and powerless.

The first step to breaking the cycle is acknowledging the harm done, grieving and mourning, facing our fears, and looking at the root causes. This is scary work and can’t be done without safety and support. Thanksgiving is a perfect time to lean on that support.

Let’s look at three ways to celebrate it.

Three ways and reasons to celebrate Thanksgiving

1. The story of the Pilgrims and Wampanoag people

This story can serve as a model for how we want to be in times of division and distrust. Coming out of recent experiences of significant loss while surrounded by violence, people of two vastly different cultures found a way to come together. They put aside their differences in the spirit of peace, mutual support, and celebration.

Celebrate Thanksgiving by lifting this point of light out of the horror surrounding it, and use it as a model for how you want to be—how we can be. Facing the full history, affirming that we can do better, and taking action to heal the rift takes responsibility for breaking the cycle of intergenerational trauma.

Some ways to celebrate in this way include:

Reach out to someone different from you. Try to make a connection that seems impossible or improbable. Have a meal together. Embrace your common humanity by remembering that you both have experienced joy and harm. For an easy conversation prompt: ask them to tell you a story about their life that will help you understand how they came to be the person they are today. Direct human connection is the only way to heal division.

Take action to heal the historical rupture. The Mashpee Wampanoag are currently struggling for full tribal recognition, so offer support.

Develop awareness of Native peoples.

If you are not on the land of your ancestors, find out whose land you are on and learn about those people. Tell others. You can begin your research by going to https://native-land.ca/.

Speak about Native peoples in a respectful way. Look over this dos and don’ts guide for allies, and use it to start conversations with your friends.

Learn and teach the true history of Native people. Present these lesson plans to your teacher (Native People Today, Impact of Native Americans, and The Future is Indigenous Coloring Book) and ask them to engage in discussions about Native Americans, their history, and their impact.

Tell a new narrative. If bridging the divide directly is not accessible to you right now, use this holiday as a chance to name and support the healing of our past. Tell others how you are inspired by the courage of the Pilgrims and Wampanoag to bridge culture and division, and start telling a new narrative.

Learn Transformational Dialogue. Join me and others at a training with Bob Stains and Raye Rawls on November 29th and 30th. Participants will learn how to facilitate dialogue that can engage around deeply conflicted issues. Register here.

2. Celebrate the harvest

Celebrating the harvest is the second traditional and culturally appropriate way to celebrate Thanksgiving. Hidden in the greater story is the fact that, one way or another, almost everyone in the United States has had their connection to Earth and their ancestors interrupted.

Nonetheless, we all have Indigenous roots, so we all come from healing traditions. We all are somewhere and all came from somewhere. Celebrating the harvest is a tradition from cultures all over the world. At the time, it was a thing in England (Harvest Home), and there were definitely Native harvest celebrations. It served as a common language for the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag.

Harvest festivals are a time to remember your relationship with food, the seasons, the land, and the water. They are an opportunity to celebrate the ultra-rare gift of being alive on an abundant planet.

Here are some ways to turn your Thanksgiving dinner into a harvest celebration:

Use locally grown food or food that’s in season.

Got something edible growing in your garden? Eat it.

Learn a Native American recipe, learn a recipe of your ancestors, or do both and serve them together.

Make a toast to the land, the farmers, the sun, and the cycles.

Quietly go outside, put your hands in the dirt and say, “thank you.”

3. Use Thanksgiving as a chance to seek forgiveness

Speaking of saying thanks, the tradition of Thanksgiving is about a lot more than saying what we are grateful for. “Thanksgiving” was a tradition that rose along with the Church of England, and the Puritans brought it to the Americas.

For them, Thanksgiving began with a day of fasting followed by a feast. As a religious rite, it was a time to repent for our wrongdoings and thank God for mercy and forgiveness.

I’ve written before about forgiveness, but for now, I’ll repeat what I think is the most important lesson I’ve learned about it: Forgiveness is not about saying there was no harm. Forgiveness only has meaning if there was harm. Instead, forgiveness is a personal choice to relinquish your right to recompense from the other person. And it’s an essential part of releasing yourself and others from the cycle of violence.

How to celebrate this way:

Take a moment to remember ways that you have been or have hurt others. A shortcut here is to reflect on points of resentment.

Feel what you feel about it, and allow yourself to grieve.

Try to identify the root causes and recognize that there are multiple perspectives.

Talk to someone you trust about it. Check to see if you are ready to forgive or ask for forgiveness.

Hint: No one owes you forgiveness, and it’s tough to forgive someone for something you can’t forgive yourself for. Often, it comes down to practicing self-forgiveness.

Apologize by demonstrating you understand (or want to understand) why the harm happened and offer to make amends.

None of this is easy, and that is why many turn to a higher power to hand this over to. If you don’t feel like you have a line to God, feel free to let the earth, moon, sun, or stars hold it for you. Another option is to write it all down and feed it to a fire. Find a way to take responsibility for what’s yours and let it go.

This process is not only healing for you and the others involved, but it’s also a critical step to liberating us from the past and growing into the best version of ourselves, individually and collectively.

The final step of breaking the cycle of violence is reconnecting with those who have harmed us and those we have harmed. Doing the work of healing the ruptures in our culture is up to all of us, and it is exactly what we need right now.

Moving forward

We need to get out of the binary good-versus-bad story of Thanksgiving. Finding a way to face the truth of our history (good and bad) is necessary to heal ourselves in the present. Healing our relationships and reconnecting with the land and our ancestors is essential if we can hope to actively work together to co-create our future. Fortunately, coded within this misunderstood holiday, we have all we need to make the repair.

So this Thanksgiving, I invite you to use it as an opportunity to remember our shared history, both the darkness and the courage many took to overcome it. Use this as a chance to refresh your relationship with the miracle of the food on your plate, the land it came from, the land you’re on, and the land that you came from. Finally, use this day as a chance to be grateful for the opportunity to give and receive forgiveness.

Make sure you’re subscribed, as I’ll be sharing an updated version of Abraham Lincoln’s Thanksgiving Proclamation on Thursday. I think it’s really good (if I do say so myself).

If this moves you, I encourage you to share it. With a podcast, video, and essay of this episode, there’s a version for everyone. Thank you for joining me for this story.

Have you subscribed to the Omni-Win Project Podcast yet? Find it on your preferred platform and join the co-creation journey. Don’t miss your chance to make a difference.

Check out the Omni-Win Project website and follow me on other platforms.

Want long-form content, authentic discussions, and weekly videos?

Subscribe to my YouTube channel

You can schedule a call with me here: https://calendly.com/duncanautrey