Interest-Based Mediation for Long-Lasting, Mutually Beneficial Change

Everyone matters, and the way we make decisions and resolve issues needs to reflect that

My previous essays introduced the Omni-Win Project, which aims to accelerate the co-creation of the future of democracy. To achieve this, we're going to need collaborative communication skills.

Today, we're going to dig deep into interest-based conflict resolution and what an interest-based political culture would look like.

Let's start with a quote from Mary Parker Follett from her book, The New State:

"There are three ways of dealing with difference: Domination, compromise, and integration. By domination, only one side gets what it wants; by compromise, neither side gets what it wants. And by integration, we find a new way by which both sides get what they wish."

When I heard that quote, I immediately thought of a conflict transformation tool:

The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI)

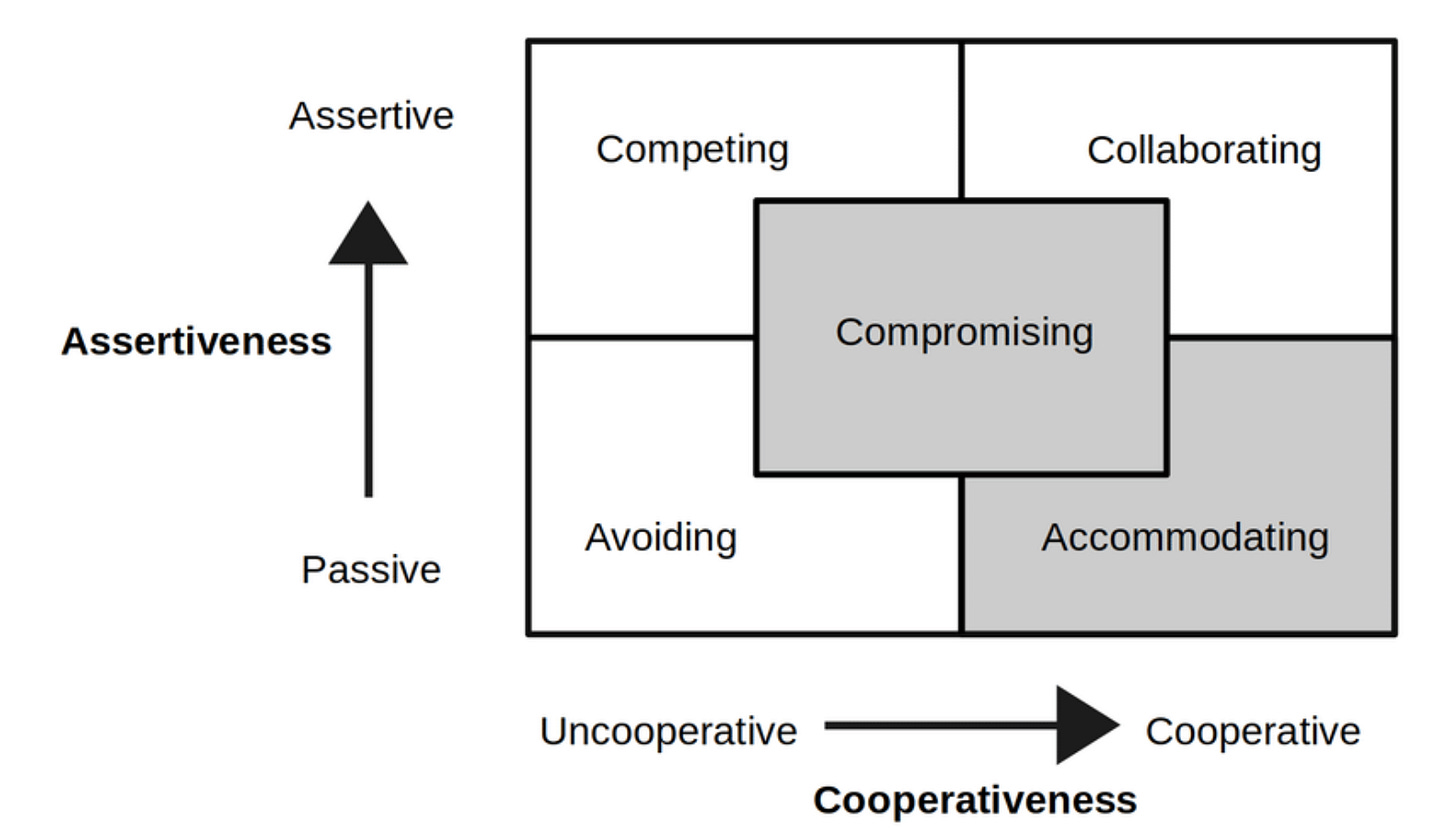

We regularly use TKI in the world of conflict transformation. The y-axis measures how important your agenda is and how much you care about getting what you want. The x-axis measures how much we value the relationship. When we look at this, there are different ways that we might respond to a conflict in different situations. Honestly, each of these makes sense in certain contexts.

Competing

Perhaps getting what you want is very important, but the relationship is of low importance. In that situation, the best conflict style or approach might be to compete with the other person to get what you want at any cost. Competing is fine if you don't care about the long-term relationship and want a short-term solution. It’s only short-term because the “opposition” might come back and fight you again. If you don't include them now, you might have to deal with them later.

Accommodating

The other extreme is accommodation. Here, you really care about the relationship but not about what you want. You focus on letting the other person have what they need. Accommodation can be great if you have a long-term relationship, and that's what's most important to you. It only works if you’re okay with not getting what you need.

Avoiding

Avoidance is when you don't care about your agenda or the relationship, so you can just avoid the conflict. You don't need to talk to the other person or ask for what you want. You're not going to get it if you don't ask for it, and you won’t be in relationship with this person because you're not talking about what's important to you.

Compromising

Often, we think about compromise, which is right in the middle. As Mary Parker Follett says, compromise is where no one really gets what they want, but everyone gets some of what they want. It can be useful when you have a short-term goal: Some things are just transactional. If there's truly a choice and mutually exclusive possibilities or needs, this can be fine because you can figure out the halfway point.

Here's an example of compromise: Let's say we're trying to decide what movie to see. The compromise would be picking a movie that both people are kind of into, but neither is watching the movie they really want to see.

Collaborating

Collaboration is the key, and it's a magical place where everyone is getting what they want. In a collaborative space, your needs matter, and you want to work with the other person to maintain your relationship. Essentially, this is the best of both worlds.

To do this, you have to engage with the other side. Now, that's not so hard when deciding on movies with your friends, but talking across the political divide is much trickier. Thankfully, we have tools, dialogue, and mediation that make this possible. It takes a little more time upfront, but you get long-term output.

Collaboration is valuable when there are issues that will benefit from multiple perspectives. It’s ideal for ongoing relationships where you're looking for a long-term sustainable solution. Those are the kind of conversations we need to have regarding our politics. We’re all going to continue being in relationship, so we need to resolve our political conflicts sustainably.

They are complex, we need many perspectives, and we need durable and adaptable solutions as these issues keep evolving. What's more, once you've learned how to collaborate, you know how to continue collaborating, and you can keep improving. But how do we do this collaboration thing?

Dealing with conflict

Let's look at the essence of mediation and dialogue: These techniques surface underlying interests and needs. We often use an iceberg model and start by talking about what we're conflicting over. This is the stuff that's above the surface.

In a political context, it might be policies that we're fighting over, like the specific language. Underneath all of that, we're trying to meet our needs and interests. In the mediation field, we know how valuable it is to recognize those underlying needs and interests. Only when we surface them can we understand what's really going on. From there, we can often find strategies that meet everyone's needs and interests.

The problem? That requires us to actually care about each other's interests and needs, and with our current rivalrous society, that's not our number one priority.

Let me tell you about the interest-based relational (IBR) approach to conflict resolution. It's a concept that Roger Fisher and William Ury developed in their 1981 book "Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In.”

I learned about IBR through my mentor, Kenneth Cloke. There are three ways we can resolve conflict: Through a power-based approach, a rights-based approach, or an interest-based approach.

The power-based approach

This approach is the oldest and sometimes the most familiar way of dealing with conflict. It's simple: Whoever has the most power wins. It’s why we use violence to resolve conflict; if someone can knock you out, they win. If you feel threatened, maybe you'll just say, “Okay, whatever you want,” because you feel unsafe and powerless.

Of course, we also have power in our politics which shows up as everything from protests to elections. It's all about trying to draw attention to the things we want, whether that's getting the person we want into power or elevating the cause we're interested in. It can become dangerous as some people cause pain and suffering to get leaders to pay attention to them.

The power-based approach is certainly effective, but it's in that competing category. It's a win-lose process. As long as you keep power, you win, but you'll be on the losing side once you lose that power. It's not the best way of resolving conflict.

The rights-based approach

The second way of resolving conflict is the rights-based approach. This is why we have laws in our society, an amazing technology we've created for ourselves. The idea of rights is to create rules that apply to everyone no matter how much power they have. However, there are a couple of disadvantages of a rights-based approach.

Often, people in power write our laws. Our legal system and legislation aren't actually representing the people. Our “representatives” don't represent us. Our legislators don't care about what people want. A corrupt system writes our laws.

This reminds me of a quote attributed to Otto von Bismarck:

“If you like laws and sausages, you should never watch either one being made.”

It's not a pretty process, and we don't necessarily trust the people making the rights.

Rights draw a line in the sand about what is and isn't okay and what's right and wrong. It creates winners and losers, and it will never be nuanced or detailed enough. We're never going to have sustainable laws because they can always change.

Anyone taking a case to court knows that the judge will be making a decision where someone loses and another wins. It's not always clear how that will work, as many elements are at play in many cases. How does the judge decide who’s right or wrong?

It doesn't work very well because we are complex. We have many different things going on. The issues we're dealing with are too complicated to be written down on paper or boiled down into a simple decision by a judge.

The interest-based approach

Interest-based conflict resolution acknowledges that diversity is an advantage; we need different people's perspectives. They ensure that we address what's important to the people involved in any situation. Ken Cloke has three interest-based definitions of politics. If we look at politics through an interest-based lens, how might we understand this whole political process that we're in?

One of them is thinking about politics as a social problem-solving process. We know there are diverse perspectives and viewpoints, and there are various ways of addressing our problems.

Using an interest-based approach reminds us that we can solve problems better if we use all the different perspectives. Our political process is a way of getting everyone’s voices together to solve problems in the most sustainable and effective ways.

We can also view politics as a large group decision-making process. As a country, we're trying to make decisions for over 300 million people. Having consensus and including everyone in the process gives us a stronger democracy. Our current representative system is not including all of our voices or helping us agree; it’s actually fueling polarization.

The whole point of our political process is to make decisions. That's a really important thing to remember. We need consensus because if we have more people agreeing with the decisions we're making, they'll be more effective.

From an interest-based perspective, the third definition of politics is to think about politics as a conflict resolution process. In a certain way, our entire political system and democratic structure are just ways to resolve conflict. The writers of the Constitution were very clear that we're going to have to make decisions. Disputes are a natural part of the process because we're going to disagree.

There are many tools and structures to ensure that we can resolve conflict without going to war or reverting to a power-based approach. We need our process to fully address the complex issues. It must be egalitarian: No one should have to win or lose. In our current political process, we all win, or we all lose.

How can we make good decisions?

So, how do we understand our current political conflict right now? What is going on? I'll provide links about where you can find some of this information. Ken Cloke and I have written a piece about the sources of political and social conflict, which is in the conflict literacy framework of the DPACE Initiative.

For us to make good decisions, we need three things:

To know what we're dealing with

Respectful relationships

A high-quality process

What we need: To understand what we're dealing with

We need high-quality content and shared information, so we know exactly what we're dealing with. We have to be very clear about what we're talking about, the variables we're measuring, our goal, and the question we're trying to answer. Say you're stuck in a conflict. If you can figure out what you're trying to achieve, so both people agree, you're more than halfway to your solution. It's an important first step.

What we have: Fake news and uncertainty

Information is a big challenge. As we're learning about social media and fake news, everyone's accusing each other of having biased or incorrect information. We're not clear about the information we need to be using as a culture.

We're also struggling with understanding the question we're trying to answer in conflict. Often, two people argue about two totally different things.

What we need: Respectful relationships

We also need high-quality, respectful relationships. We need people that trust, respect, and engage with each other. Everyone needs to be able to listen.

What we have: Polarization

Because of the depth of polarization, there are a lot of broken relationships. Trust, respect, and mutual consideration are missing.

What we need: A high-quality process

The third thing we need is a high-quality process. One that can create win-win outcomes, integrate all the information, and honor different perspectives. From there, we can develop mutually agreeable outcomes or solutions that people can live with. This might sound like fantasy, but we have the processes for these conversations.

What we have: A win-lose process

If we look at our entire political and democratic process, it’s win-lose. We are nowhere near a conversation about win-win outcomes that work for everyone.

We'll jump into process shortly, but I want to discuss why we're having such a hard time. We're struggling with our relationships and getting clearer about our content. But why?

Culture War 2.0

We're in something that people are calling the “political-industrial complex.” This is keeping us divided. (I’ll be exploring this system in an essay soon, so keep an eye out for that if you're interested in learning more.)

Our ideology is an issue, too. We're in a big culture war. Peter Limberg calls this “Culture War 2.0,” remarking that we divide ourselves into different tribes with an ideology and leader. We each have our models for thinking about things, specific values, and goals we're trying to achieve. Peter Limberg and Conor Barnes call these “memetic tribes.”

Yes, memes are an internet thing, but memes are also a seed of culture, an origin of thought, or a belief system. So, we're divided into these different tribes believing in distinct things. Now, these tribes are fighting for their causes. When they feel threatened, they fight to the death. Not only this, they're super optimistic and very confident that they've figured out the answer to any given issue.

Here are a few of the memetic tribes that Peter Limberg and Conor Barnes have identified:

Social Justice Activists (SLAs)

Black Lives Matter (BLM)

Democratic socialists

Tea Party

QAnon

Evangelical Christians

We all have models and leaders, and we believe that we have the answers to all the problems. I'm part of a memetic tribe of mediators and conflict resolution practitioners. In our defense, mediation can solve a lot. (But I digress.)

So, we have memetic tribes, a culture war, and everyone's fighting to the death to ensure we bring their goals forward. These are rooted in deep values and ideology.

Ryan Nakade is my friend and colleague, and he’s the creator of the Meta-Ideological Politics podcast. (He will also be a guest on the Omni-Win Project podcast!) Ryan has an article called "Why it's impossible to abandon ideology and what to do instead."

He has four reasons why we can't get past ideology:

1) It structures what we can see.

2) It informs what we consider a problem.

3) It constructs potential solutions to the problem.

4) It judges value trade-offs (what we care about).

What can we see?

First of all, ideology structures what we can see, and it also tells us what we can't see. Ryan points out that everything looks like a nail if the only tool you have is a hammer. But if you don't have a hammer, you can't figure out what to do with a nail.

Our ideology helps us think about what's important and what's not important. We have certain things in our blind spots, and we fixate on other things.

What's the problem?

Ideology shows us what is or isn't a problem. Every doctrine will identify a different issue. Guess what? All problems are important; we're just looking at different ones as we all have a unique view.

What's the solution?

With ideology, we can recognize solutions to the problem. Even if we agree on the issue, our principles will give us different ways of resolving it. This diversity of perspectives helps us solve problems sustainably.

What are the trade-offs?

As multiple approaches or solutions are really helpful, ideologies let us see the value trade-offs. What's most important and what's least important?

Ideology drives all these things, so we need to take it into consideration. Peter Limberg expands on his memetic tribe thoughts in “Memetic Mediation: The Hard Problem of the Culture War.” He says we need people with the skills to mediate across these ideological divides. Combining these different ideas, problems, and unique solutions is vital.

If we can bring all of that together using interest-based mediation, we can find mutually agreeable solutions. I totally agree with the call for memetic mediation, and there are many great mediators.

In the DPACE Initiative (the Democracy, Politics, and Conflict Engagement Initiative,) we have hundreds of mediators that are super excited to help out, and we have the tools.

This week’s recommendation

For their mediation series, Rebel Wisdom brought together Peter Limberg and Diane Musho Hamilton, a Zen Buddhist practitioner and mediator, for a piece called “Making Mediation Sexy?”. They had a wonderful conversation about ideological mediation, and they came up with a couple of things that I found interesting.

We know conflict is exciting. It’s very engaging, gets our blood up, and draws us in. While it's energizing, unity and collaboration are satisfying and comforting. There's something special about taking our differences and figuring out where we can find sameness and unity. We need to lift that spirit up.

Another interesting takeaway was teaching people how to fight better, as they may fight less. It’s something that I’ve thought about as well. Once we understand the nature of conflict, which is fundamental to understanding conflict transformation, we can learn to be high-quality fighters.

If we become very skilled fighters, we’re less likely to get into conflict because we know we could destroy the other person. I'm all about paradoxes, so I'm into it.

The mediation world wants people to be more capable at saying what they need to say. We also want people to listen to the other side and argue about the highest caliber elements of an issue.

We need to bring more mediators, conflict resolution practitioners, conflict system designers, and dialogue facilitators into our political discussions. It's fundamentally important, and it’s one of the huge goals of the Omni-Win Project.

Next week, I’ll be talking more about interest-based mediation and how we can improve our conversations—watch this space.

If you prefer to watch your content, here’s a video on the topic of this essay:

You can find more information about the work I do in conflict transformation on my website: http://www.omni-win.com

You can schedule a call with me here: https://calendly.com/duncanautrey

Don’t forget to check out the rest of my posts as I discuss how we can work together to ensure we all win.

If you’d like to see more of these weekly round-up posts, subscribe to Omni-Win Visions here on Substack:

It would also be great if you could subscribe to my YouTube channel, where you can watch more of my long-form content, authentic discussions, and weekly content: